THE FOOD PROTOCOL FOR THE CULTURAL VALUES

Eating is taken very seriously in Turkey. It is inconceivable for the household members to eat alone, raid the refrigerator, or eat on the “go”, while others are at home.

It is custom to have three “sit-down meals” a day. Breakfast or “kahvaltì” (literally, “foundation for coffee”), typically consists of bread, feta cheese, black olives and tea. Many work places have lunch served as a contractual fringe benefit. Dinner starts when all the family members get together and share the events of the day at the table. The menu consists of three or more types of dishes that are eaten sequentially, accompanied by salad. In summer, dinner is served at about eight. Close relatives, best friends or neighbors may join meals on a “walk-in” basis. Others are invited ahead of time as elaborate preparations are expected. The menu depends on whether alcoholic drinks will be served or not. In the latter case, the guests will find the meze spread ready on the table, frequently set up either in the garden or on the balcony. The main course is served several hours later. Otherwise, the dinner starts with a soup, followed by the meat and vegetable main course, accompanied by the salad. Then the olive-oil dishes such as the dolmas are served, followed by dessert and fruit. While the table is cleared, the guests retire to the living room to have a tea and Turkish coffee.

Women get together for afternoon tea at regular intervals (referred to as the “7-17 days”) with their school-friends and neighbors. These are very elaborate occasions with at least a dozen types of cakes, pastries, finger foods and böreks prepared by the host. The main social purpose of these gatherings is to share information and experience about all aspects of life, public and private. Naturally, one very important function is the propagation of recipes. Diligent exchanges occur while women consult each other on their innovations and solutions to culinary challenges.

Women get together for afternoon tea at regular intervals (referred to as the “7-17 days”) with their school-friends and neighbors. These are very elaborate occasions with at least a dozen types of cakes, pastries, finger foods and böreks prepared by the host. The main social purpose of these gatherings is to share information and experience about all aspects of life, public and private. Naturally, one very important function is the propagation of recipes. Diligent exchanges occur while women consult each other on their innovations and solutions to culinary challenges.

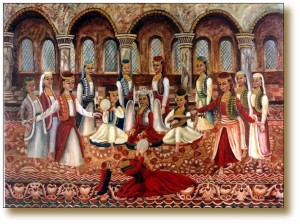

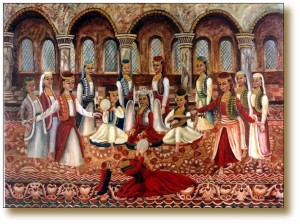

By now it should be clear that the concept of having a “pot-luck” at someone’s house is entirely foreign to the Turks. The responsibility of supplying all the food squarely belongs to the host, who expects to be treated in the same way in return. There are two occasions where the notion of “host” does not apply. One such situation is when neighbours collaborate in making large quantities of food for the winter such as “tarhana” – dried yogurt/tomato soup or noodles. Another is when families get together to go on a day’s excursion to the country-side. Arrangements are made ahead of time as to who will make the köfte, dolma, salads, pilafs and who will supply the meat, the beverages and the fruits. The “mangal” – the copper charcoal burner, kilims, hammocks, pillows, musical instruments such as saz, ud, or violin, and samovars are loaded up for a day trip.

A “picnic” would be a pale comparison to these occasions, often referred to as “stealing a day from fate”. Kücüksu, Kalamis, and Heybeli in old Istanbul used to be typical locations for such outings, as many songs tell us. Other memorable locations include the Meram vineyards in Konya, Hazer Lake in Elazig, and Bozcaada off the shores of Canakkale. Commemorating two Saints : Hizir and Ilyas (representing immortality and abundance), the May 5 Spring Festival (Hidirellez) would mark the beginning of the pleasure-season (safa), with romantic affairs, lots of poetry, songs and, naturally, good food.

A “picnic” would be a pale comparison to these occasions, often referred to as “stealing a day from fate”. Kücüksu, Kalamis, and Heybeli in old Istanbul used to be typical locations for such outings, as many songs tell us. Other memorable locations include the Meram vineyards in Konya, Hazer Lake in Elazig, and Bozcaada off the shores of Canakkale. Commemorating two Saints : Hizir and Ilyas (representing immortality and abundance), the May 5 Spring Festival (Hidirellez) would mark the beginning of the pleasure-season (safa), with romantic affairs, lots of poetry, songs and, naturally, good food.

A similar “safa” used to be the weekly trip to the Turkish Bath. Food prepared the day before, would be packed on horse drawn carriages along with fresh clothing and scented soaps. After spending the morning at the marble wash-basins and the steam hall, people would retire to the wooden settees to rest, eat and dry off before returning home.

These days, such leisurely affairs are all but gone, spoiled by modern life. Yet, families still attempt to steal at least one day from fate every year, even though fate often triumphs. Packing food for trips is so traditional that even now, it is common for mothers to pack some köfte, dolma and börek to go on an airplane, especially on long trips much to the bemusement of other passengers and the irritation of flight attendants. But seriously, given the quality of airline food, who can blame them?

Weddings, circumcision ceremonies, holidays are celebrated with feasts. At a wedding feast in Konya, a seven course meal is served to the guests. The “sit-down meal” starts with a soup, followed by pilaf and roast meat, meat dolma, and saffron rice-a traditional wedding dessert. Börek is served before the second dessert, which is typically the semolina helva. The meal ends with okra cooked with tomatoes, onions, and butter with lots of lemon juice. This wedding feast is typical of Anatolia, with slight regional variations. The morning after the wedding, the groom’s family sends trays of baklava to the bride’s family.

During the holidays, people are expected to pay short visits to each and every friend within the city, visits which are immediately reciprocated. Three or four days are spent going from house to house, so enough food needs to be prepared and put aside to last the duration of the visits. During the holidays, kitchens and pantries burst at the seams with böreks, rice dolmas, puddings and desserts that can be put on the table without much preparation.

Deaths are also occasions for cooking and sharing food. In this case, neighbors prepare and send dishes to the bereaved household for three days after the deaths. The only dish prepared by the household of the deceased is the helva which is sent to the neighbors, who will remember and pray for the departed. In some areas, it is a custom for a good friend of the deceased to begin preparing the helva, while recounting fond memories and events. Then the spoon would be passed to the next person who would take up stirring of the helva and continue reminiscing. Usually the helva will be done by the time everyone in the room has had a chance to speak and stir the helva. This wonderful simple ceremony, by making people left behind talk about happier times, lightens up their grief momentarily and strengthens the bond between them.

kaynak

http://www.ottomansouvenir.comdan faydalanılmıstır.

Women get together for afternoon tea at regular intervals (referred to as the “7-17 days”) with their school-friends and neighbors. These are very elaborate occasions with at least a dozen types of cakes, pastries, finger foods and böreks prepared by the host. The main social purpose of these gatherings is to share information and experience about all aspects of life, public and private. Naturally, one very important function is the propagation of recipes. Diligent exchanges occur while women consult each other on their innovations and solutions to culinary challenges.

Women get together for afternoon tea at regular intervals (referred to as the “7-17 days”) with their school-friends and neighbors. These are very elaborate occasions with at least a dozen types of cakes, pastries, finger foods and böreks prepared by the host. The main social purpose of these gatherings is to share information and experience about all aspects of life, public and private. Naturally, one very important function is the propagation of recipes. Diligent exchanges occur while women consult each other on their innovations and solutions to culinary challenges.

By now it should be clear that the concept of having a “pot-luck” at someone’s house is entirely foreign to the Turks. The responsibility of supplying all the food squarely belongs to the host, who expects to be treated in the same way in return. There are two occasions where the notion of “host” does not apply. One such situation is when neighbours collaborate in making large quantities of food for the winter such as “tarhana” – dried yogurt/tomato soup or noodles. Another is when families get together to go on a day’s excursion to the country-side. Arrangements are made ahead of time as to who will make the köfte, dolma, salads, pilafs and who will supply the meat, the beverages and the fruits. The “mangal” – the copper charcoal burner, kilims, hammocks, pillows, musical instruments such as saz, ud, or violin, and samovars are loaded up for a day trip.

A “picnic” would be a pale comparison to these occasions, often referred to as “stealing a day from fate”. Kücüksu, Kalamis, and Heybeli in old Istanbul used to be typical locations for such outings, as many songs tell us. Other memorable locations include the Meram vineyards in Konya, Hazer Lake in Elazig, and Bozcaada off the shores of Canakkale. Commemorating two Saints : Hizir and Ilyas (representing immortality and abundance), the May 5 Spring Festival (Hidirellez) would mark the beginning of the pleasure-season (safa), with romantic affairs, lots of poetry, songs and, naturally, good food.

A “picnic” would be a pale comparison to these occasions, often referred to as “stealing a day from fate”. Kücüksu, Kalamis, and Heybeli in old Istanbul used to be typical locations for such outings, as many songs tell us. Other memorable locations include the Meram vineyards in Konya, Hazer Lake in Elazig, and Bozcaada off the shores of Canakkale. Commemorating two Saints : Hizir and Ilyas (representing immortality and abundance), the May 5 Spring Festival (Hidirellez) would mark the beginning of the pleasure-season (safa), with romantic affairs, lots of poetry, songs and, naturally, good food.

A similar “safa” used to be the weekly trip to the Turkish Bath. Food prepared the day before, would be packed on horse drawn carriages along with fresh clothing and scented soaps. After spending the morning at the marble wash-basins and the steam hall, people would retire to the wooden settees to rest, eat and dry off before returning home.

These days, such leisurely affairs are all but gone, spoiled by modern life. Yet, families still attempt to steal at least one day from fate every year, even though fate often triumphs. Packing food for trips is so traditional that even now, it is common for mothers to pack some köfte, dolma and börek to go on an airplane, especially on long trips much to the bemusement of other passengers and the irritation of flight attendants. But seriously, given the quality of airline food, who can blame them?

Weddings, circumcision ceremonies, holidays are celebrated with feasts. At a wedding feast in Konya, a seven course meal is served to the guests. The “sit-down meal” starts with a soup, followed by pilaf and roast meat, meat dolma, and saffron rice-a traditional wedding dessert. Börek is served before the second dessert, which is typically the semolina helva. The meal ends with okra cooked with tomatoes, onions, and butter with lots of lemon juice. This wedding feast is typical of Anatolia, with slight regional variations. The morning after the wedding, the groom’s family sends trays of baklava to the bride’s family.

During the holidays, people are expected to pay short visits to each and every friend within the city, visits which are immediately reciprocated. Three or four days are spent going from house to house, so enough food needs to be prepared and put aside to last the duration of the visits. During the holidays, kitchens and pantries burst at the seams with böreks, rice dolmas, puddings and desserts that can be put on the table without much preparation.

Deaths are also occasions for cooking and sharing food. In this case, neighbors prepare and send dishes to the bereaved household for three days after the deaths. The only dish prepared by the household of the deceased is the helva which is sent to the neighbors, who will remember and pray for the departed. In some areas, it is a custom for a good friend of the deceased to begin preparing the helva, while recounting fond memories and events. Then the spoon would be passed to the next person who would take up stirring of the helva and continue reminiscing. Usually the helva will be done by the time everyone in the room has had a chance to speak and stir the helva. This wonderful simple ceremony, by making people left behind talk about happier times, lightens up their grief momentarily and strengthens the bond between them.

kaynak

http://www.ottomansouvenir.comdan faydalanılmıstır.<-->

- Genel

- Yorumlar(0)